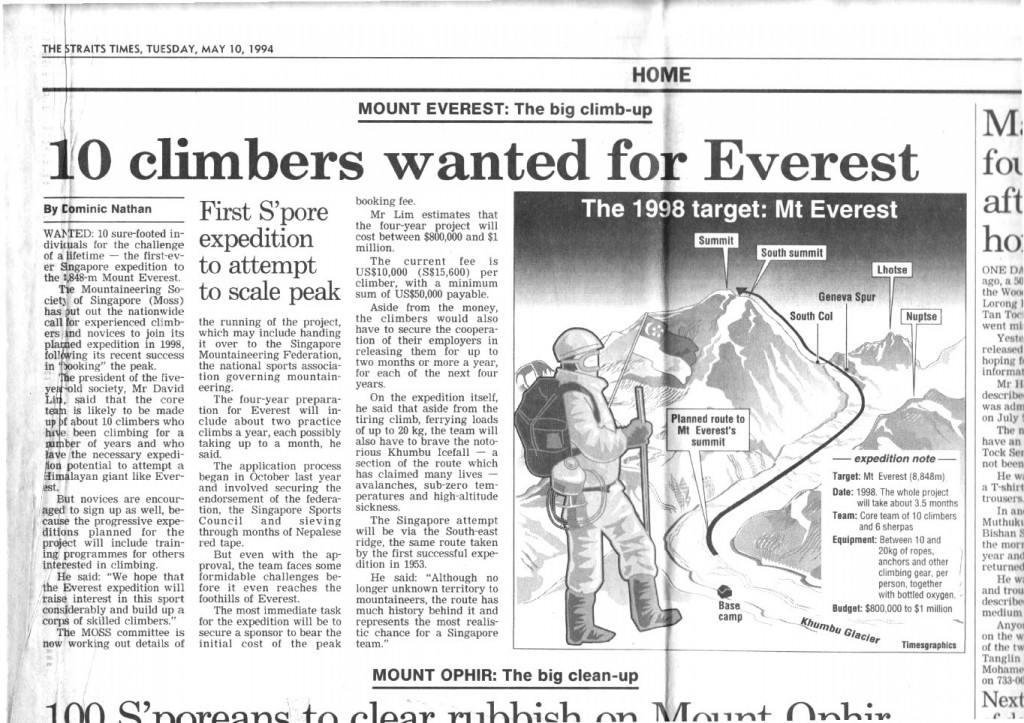

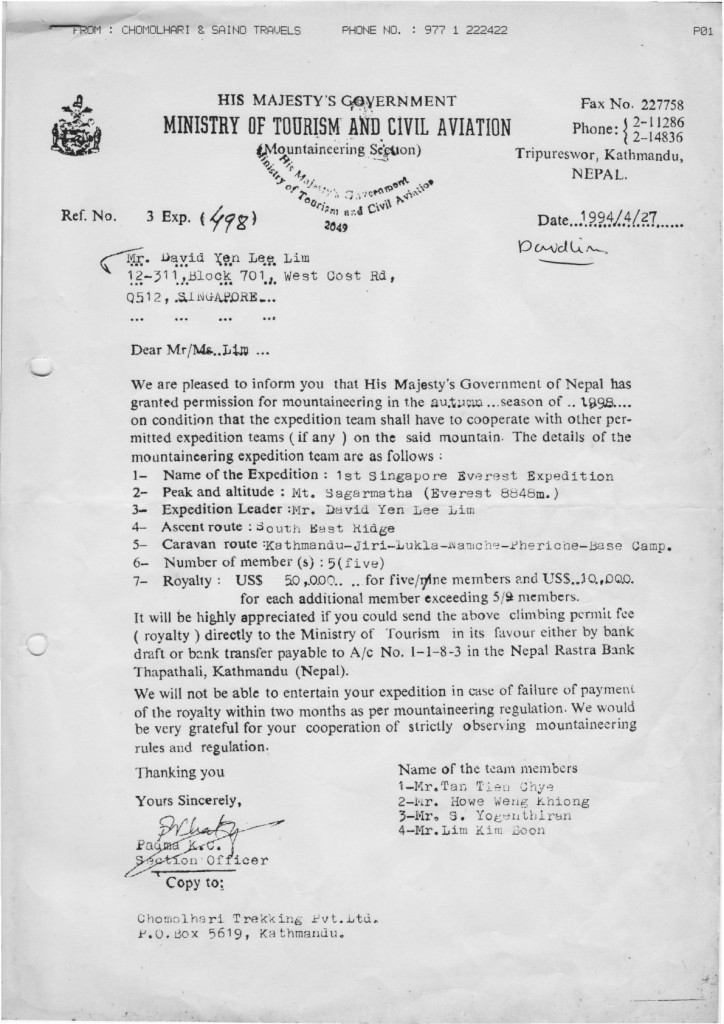

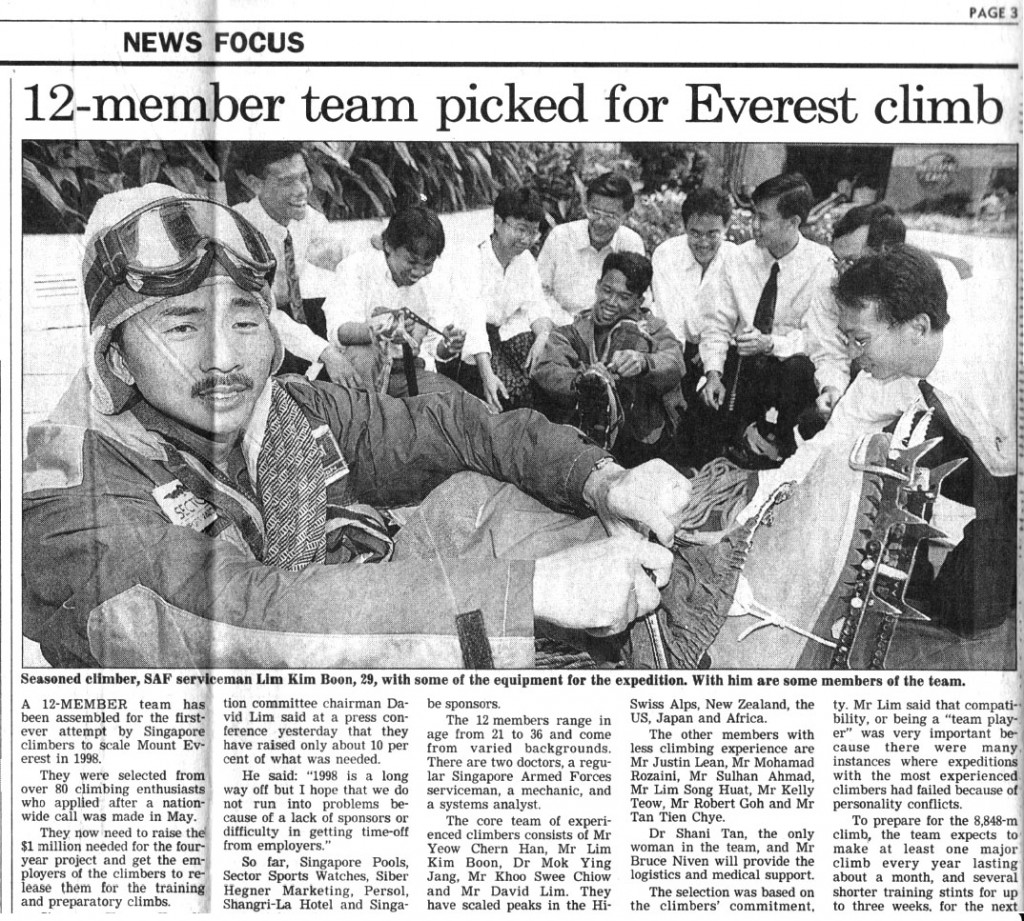

Most of 1994 was spent organising a team, as well as beginning the fundraising drive. This was largely spearheaded by David Lim and Justin Lean, requiring significant after -hours work, lunch-time meetings with prospects and so on. As usual, there were some genuine well-wishers and some timewasters who realised that they couldn’t deliver what they promised. Stories in the press at that time focused on the large sponsorship and team challenge.

AA major boost happened in March 1995 when, after a request was sent, the the President of the Republic, Ong Teng Cheong , agreed to be the Expedition Patron. Mr Ong, unbeknownst to us at that time, had stuck his neck out, ignoring the advice of some of his advisors who warned about supporting a venture that could “fail”. Apparently, his response to these risk-averse people were ” That is exactly why I should give them my support”. These and other nuggets were only revealed much later after the expedition concluded.

In a letter of encouragement to the team members, President Ong wrote:

“Mountaineering is not a tradition in Singapore. Only people with strong determination and spirit of adventure like you will set your sights on the conquest of Mount Everest. Whether you are climbers or members of the support team, you are all pioneers with the courage to try and succeed.”

Meeting the President at his official residence, the Istana, in March 1996 for an update. From L to R: Lim Kim Boon. David Li, President Ong Teng Cheong and Rob Goh.

The team began training with some members undertaking smaller trips with each other to places like Mt Kinabalu and the NZ Alps, where peaks like Mt Cook were climbed. Planning began in earnest to organise a whole-team expedition to climb Kun, part of the 7000m Nun-Kun peaks in Ladakh, India.

This expedition took place in August and met with bad weather. They were froced to try a new route on Nun (which was not even planned for)after deep snow made it impossible to reach Kun’s basecmp. WIth little time left, the team regrouped in Leh, the capital of Ladakh and re-launched themselves at another objective organised on the fly – Stok Kangri – a simple 6000-metre peak. Four members, David Lim Rob Goh, YJ Mok and SC Khoo summitted

This expedition took place in August and met with bad weather. They were froced to try a new route on Nun (which was not even planned for)after deep snow made it impossible to reach Kun’s basecmp. WIth little time left, the team regrouped in Leh, the capital of Ladakh and re-launched themselves at another objective organised on the fly – Stok Kangri – a simple 6000-metre peak. Four members, David Lim Rob Goh, YJ Mok and SC Khoo summitted

The team returned to review the lessons of the climb and continued the quest to raise the nearly $1 million SG dollars needed for the climb. David’s leadership had been confused at times, and some members had behaved selfishly. All in , it was a sobering lesson that the team dynamics needed work.

Below: David, at Camp 1, with Nun in the background

Above: The 6125m, Stok Kangri

1996 was a more hopeful year, with the team succeeding on a number of alpine summits in the Swiss and French Alps in the summer of that year. David Lim and Justin Lean had also pulled off some difficult ascents in the NZ Alps on Mt Tasman. The team also acquired new sponsors Ricola. They would be the single largest non-government linked sponsor with $65000 invested in the expedition. Contrary to what many Singaporeans then and now believed, the TOTAL financial support of the Singapore government and government-linked organisations only amounted to 11% of the total needed for Everest in 1998. ( inset left: David Lim high on Syme Ridge, Mt Tasman, Jan 1996)

1996 was a more hopeful year, with the team succeeding on a number of alpine summits in the Swiss and French Alps in the summer of that year. David Lim and Justin Lean had also pulled off some difficult ascents in the NZ Alps on Mt Tasman. The team also acquired new sponsors Ricola. They would be the single largest non-government linked sponsor with $65000 invested in the expedition. Contrary to what many Singaporeans then and now believed, the TOTAL financial support of the Singapore government and government-linked organisations only amounted to 11% of the total needed for Everest in 1998. ( inset left: David Lim high on Syme Ridge, Mt Tasman, Jan 1996)

However during this time, the naysayers and cynics also became more vocal. In 1996, an opinion piece, and an exceedingly poor piece of journalism for all its factual errors) made fun of the climb, denigrating the climbers et al was published in the major media. Written by an ‘award-winning’ journalist, you wonder if that award was for being Jerk of the Year – not to mention OpEd With The Most Factual Errors. For goodness, sake , at least if the sarcasm and critique had anything like the class of a Salon.com piece, it would have been bearable. As is… we had to put up with this twaddle. Singapore’s largest climbing shop carried, for a long time, a news clipping of us that was parodied by an unknown cartoonist and was displayed for all to see – until we shut our critics up. Such occurrences were part and parcel of pulling off something difficult, and unwelcome in the face of tawdry, and mediocre journalism, not to mention mediocre minds. The Tall Poppy Syndrome comes to mind as well.

Left: David Lim on the Ice nose route on Piz Scersen in the Bernina range of the Swiss Alps, July 1996

Left: David Lim on the Ice nose route on Piz Scersen in the Bernina range of the Swiss Alps, July 1996

In September, the team, now somewhat smaller with several voluntary departures, went to make an attempt at a 7000-metre peak, Putha Hiunchuli by the North Face. This was the first time any SE Asian team had attempted a peak f this scale. Located in mid-west Nepal, the peak had been climbed infrequently owing to the challenging access. After some bad weather in the initial stages, David Lim and SC Khoo stood on the summit. A few days later MB Tamang and Rob Goh did the same. YJ MOk and S. Yogenthiran had to retire for health reasons.

Putha Hiunchuli was a tremendous success at a time when there were nagging doubts if the team could pull it all together on a climb. Despite differences and some obvious dislike for each other by some team members, and some selfishness, the team was functioning above expectations. Only the money issues were unresolved, and team had to consider how they would find another few hundred thousand dollars to complete the funding for Everest in 1998.

Below: SC Khoo and David Lim on the 7246m summit of Putha Hiunchuli a.k.a Dhaulagiri VII

Other climbs of note that year were climbs by Justin, Shani and Rozani on the Chulu Peaks in November.

Other climbs of note that year were climbs by Justin, Shani and Rozani on the Chulu Peaks in November.

First, previous night’s snow must be cleared (if any) unless you prefer to work with an aqualung. The “king a la king” – our two solar panels are then taken out gently to be laid on the ground outside the comms tent. Actually, these solar panels are supposed to be military standards issue, but I think Pentagon didn’t think that mil-specs include being exposed to -30 deg C at night and 30 deg C during the day. We actually found two broken wires inside one solar panel and I had to “operate” on it to solder the broken wires together. Luckily, Humpty Dumpty has some capable “king men” to glue him back!

First, previous night’s snow must be cleared (if any) unless you prefer to work with an aqualung. The “king a la king” – our two solar panels are then taken out gently to be laid on the ground outside the comms tent. Actually, these solar panels are supposed to be military standards issue, but I think Pentagon didn’t think that mil-specs include being exposed to -30 deg C at night and 30 deg C during the day. We actually found two broken wires inside one solar panel and I had to “operate” on it to solder the broken wires together. Luckily, Humpty Dumpty has some capable “king men” to glue him back!